Piracy in the Indian Ocean

Piracy ran rampant across Indian coastlines in the 16th and 17th centuries. Despite it having a lasting impact on an integral region of India, its history is still not well-known. Read on if you wish to know more about this underrated period of Indian history.

A depiction of Maratha grabs attacking an English ship in the early eighteenth century. Image Source: ResearchGate

Increasing European piracy within the Arabian Sea became a source of recurring conflict with the Mughal authorities, the foremost prominent example of which was the capture of Aurangzeb's ship Ganj-i Sawai by a pirate - Henry Every. It had been commonly believed in Surat that the servants of the country factory had dealings with English pirates. The Emperor's retaliative measures against nation factors highlight a system of balance of threats.

In about 1650 the merchant navy of Surat contained 50 ships, large and well-built. By 1701 the number of sea-going ships in Surat was a minimum of 112. Much of the Indian shipping at Surat belonged to the aristocracy, the big princely ship declining in importance only within the later seventeenth century. In respect of freight traffic, the Mughals realizing the potential of the westward trade, financed the building of ships. This reduced Indian dependence on foreign vessels but also made them vulnerable, put off and more reliant on European naval escorts. The quantity of vessels captured commensurately pushed up the coast of protection. However, this protection wasn't really adequate.

Exasperated at the breakdown of protection on the pilgrimage route, Aurangzeb ordered Sir John Gayer, the 'old' Governor and his fellow servants to be thrown into prison, an episode taken advantage of by the 'new' Company's Governor Sir Nicholas Waite (1700-08). At Masulipatam also, Aurangzeb's demand to Sir William Norris was to allow Protection to Mughal shipping. Whenever a dispute broke out between one in every of the trading companies and also the Mughal authorities, the primary step taken by the latter was to cut-off the supplies. The reply of the factors was to create prizes of Indian vessels. There have been many instances of such a policy of brinkmanship. In up to now because the European factories - until they developed into fortified settlements - were at the mercy of the Mughal, there was a balance of threats.

In a discussion on piracy the driving forces behind certain questions must be examined. European efforts at monopoly, increased piracy in Indian waters, as traders whom they dispossessed were forced to use this alternative. But only certain groups just like the Malabaris advised resistance, which too, specifically form, while others structured a modus vivendi of indirect partnerships with Europeans officials or merchants. Piracy was a natural outgrowth of European rivalries. Ships of 1 nation waylaid another, whether or not they weren't during a state of war, or had a political candidate commission.

Piracy itself was an outcome of an unlimited improvement in naval and military techniques within the ships operating within the Indian Ocean. Satish Chandra has argued that the corsairs could only succeed where their ships could outmanoeuvre or outgun a normal ship. Within this context, K.N. Chaudhuri's respect to "a transparent naval Portuguese superiority over Asian ships" must be re-examined. The Vasco da Gama period in Asian history, as Steensgaard names it, wasn't the same period of European naval superiority. Asian naval techniques and techniques were neither backward nor passive.

Portuguese ships weren't necessarily bigger than Asian; but they did carry cannon as a matter after all, while initially Asian ships didn't. Also, big wasn't always better. The slow and hulking Portuguese carracks had to offer thanks to the naval superiority of English and Dutch fleets.

The Europeans tried to control Asian commerce by cartazes and armed trade. But the maritime activities of Indian merchants couldn't really be controlled. the national issue of passes was even less effective than that of the Portuguese. It absolutely was only by the mid-eighteenth century that they were able to take over or direct Indian Ocean trade. Transport was obviously the weakest link within the far off network of oceanic trade. The pass system did interfere with its regular mechanism and revealed the insecurity of maritime routes. Piracy, whether as a manifestation of individual greed, ubiquitous brigandage or political strategy, was within the end an exercise of brute force and extortion.

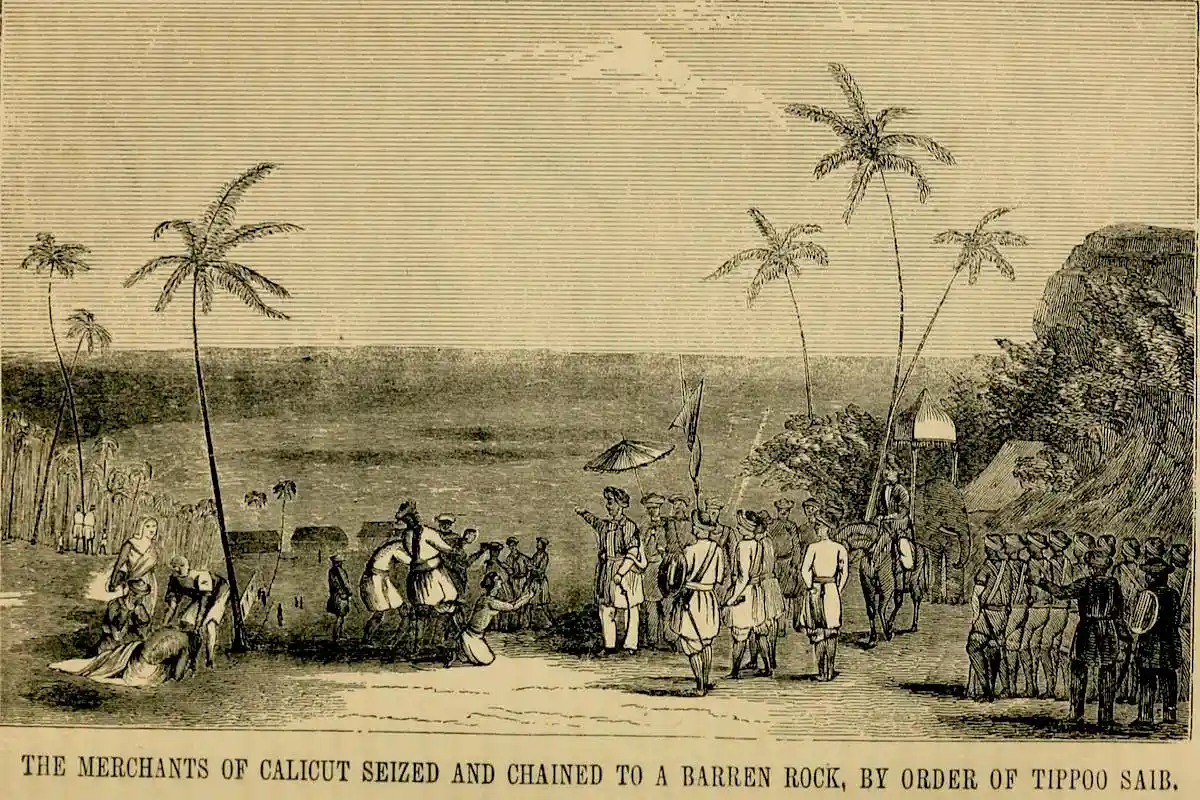

The Pirates of Malabar, and An Englishwoman in India Two Hundred Years Ago. Image Source: Columbia University.

The Mapilla Betrayal of Malabar Hindus During the Death-Dance of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. Image Source: The Dharma Dispatch.