Bansuri: Musically Fluting Through History

No one can refute the fact that music thrives in the instruments that breathe life into it. Some musical instruments become the identity of a culture, like the flute or bansuri. Can you imagine any Indian music without the heady bliss of a murali?

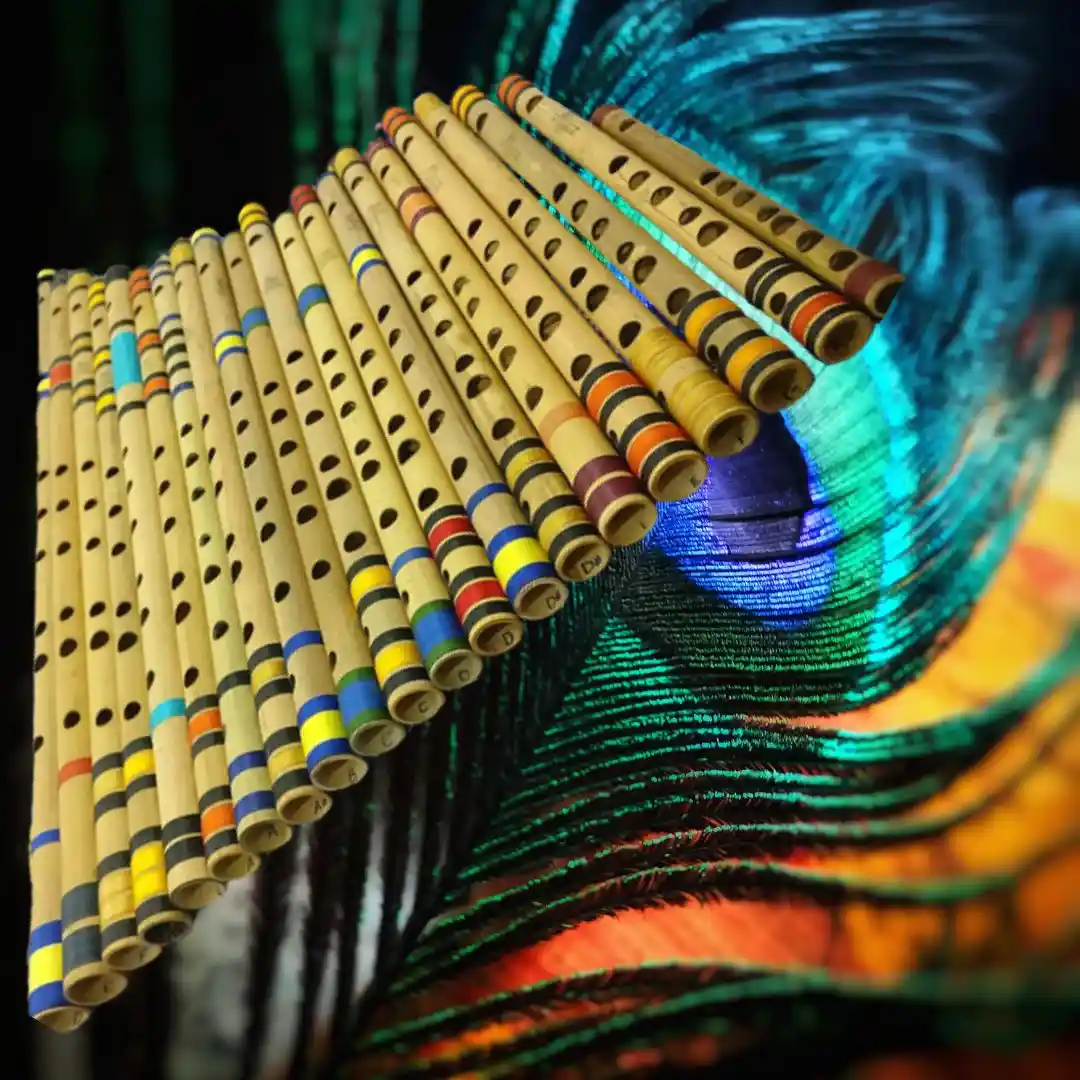

Bansuri in All Scales of Divine Glory | Source: Wikimedia, recreated in Canva

The culture of every civilisation or nation partly flows in music, and in the vast encyclopaedic nature of Indian culture, music is the bloodline of its heritage. Music encompasses and satisfies every aesthetic craving of our subcontinent, whether for spiritual or emotional expressions or even plain thoughts. Among the different types of music in the world, there are a few instruments that constitute the iconography of their form and are as old as music itself. The flute is one of them. In India, it is the iconic instrument of Lord Krishna and the associated folklore of Hindustani music, like the Raas Leela.

As Kabir once said, “The flute of the infinite is played without ceasing, and its sound is love.”

The mention of flutes in most Indian mythology and religious scriptures gleams with ancestral age in our subcontinent. The iconography of Lord Krishna and the lovelorn folktales of Radha stand on the Indian flute made of bamboo. Flutes excavated during archaeological findings across the globe have led scientists to claim them as the oldest musical instruments in the world. The most ancient flute was found in a pre-historic cave in Ulm, Germany, dating back 35,000 years. The presence of pre-historic flutes made of carved bones found in North America, China, Sumeria, and India proves that flutes were the favourite musical instrument in most parts of the world. The story of the Indian bansuri is romantic, spiritual, and a reflection of the idyllic pastoral roots of our nation.

Two Maestros of Flutists | Source: Wikimedia, recreated in Canva

The tale of the Indian flute is unique in its traditional bamboo version, where the music is created by covering and uncovering the finger holes and does not have a lineage with the Western flutes with keys that are depressed and released. This aerophone, popularly known in India as the Bansuri, played its musical role only in sweet folk music initially. Bansuri was introduced into Indian classical music by the legendary flautist, Pannalal Ghosh. He introduced the 32-inch bansuri with seven holes catering to the Indian ragas, and Pandit Raghunath Prasanna developed it, further catering to the nuances of classical music. The traditional flute works well in North Indian Hindustani music, but the South Indian Carnatic music needs the variant with eight holes, called Pullanguzhal.

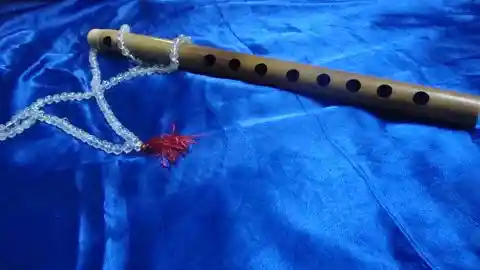

The Flute with eight finger holes, adapted for South Indian classical music | Source: Wikimedia

The flute in early medieval texts of India was referred to as vaṃśi and seen in many paintings and reliefs in temples of different traditions like Jainism or Buddhism, apart from Hinduism. The word originates from the Sanskrit word vamsha for bamboo, and the flute player in Sanskrit was called vamsika. The Buddhist stupas dated from the first century BC, found in central India, show twinned-single flutes. The Himalayan foothills have variants of flutes known as the algoza, which is a twin bansuri, a single instrument constructed with different keys to create enhanced and complex music. South India, further, has other innovative forms of flute, like the mattiyaan jodi or nagoza.

Even in Java and Bali, flutes are depicted in their temple carvings and are locally referred to as wangsi or bangsi. It sounds like the bansi, which gives one of the names for Lord Krishna – Bansi Bajayya. Bansuri, originally a Nepali word, is also mentioned as murali in some of the Indian texts. But the word murali is not specifically for the bamboo flute, rather also includes an instrument made of reed. Venu is another name found in the Indian texts derived from the Hindu texts about music and Natya-Shastra, forming the inseparable vaani-veena-venu of Indian classics. Venu stands for the flute in the post-Vedic texts and reflects on another name of Lord Krishna, Venugopal. However, in the Rigveda, the flute is referred to by names such as nadi or tunava.

An artwork depicts Venugopal | Source: Wikipedia

According to studies conducted by flute scholars like Ardal Powell, flutes were born in Greece, Egypt, and India, and the rest of the countries or civilisations adopted or adapted from these original forms. Broadly, there are two types of flutes: the fipple or whistle flute and the transverse type. Of these, the transverse type or the cross flute originally belonged only to India. Some scholars conclude that the vertical-end blown style was adopted sometime during the fifteenth century with the West-Asian advent in the subcontinent.

Rumi encapsulated the essence so well when he said, “Play the flute of felicity! You, yourself, are the melody.”

There are many folktales surrounding the bansuri along with religious leanings towards it. To know them, stay tuned for a musical sequel to this story. Like the swara of the flowing river, the frenzy of gathering clouds, the bliss of ardent devotion, the tears of virah vedana, and the entire gamut of emotions and nature, the bansuri has irrevocably tuned them all into our psyche forever. One cannot refute that, just as music is the elixir of life, the flute is the elixir of music.